Ethical Dimensions of Digital Feudalism in Agriculture

Foteini Zampati, Kathryn Bailey and Suchith Anand, GODAN

Nearly 800 million people currently struggle with debilitating hunger, while malnutrition is becoming increasingly common. Worldwide, nearly one in every nine people are suffering hunger, with the majority being women, elderly people and children.

Smallholders manage over 80 percent of the world’s estimated 500 million farms, providing over 80 percent of the food consumed across the developing world, and contributing significantly to poverty reduction and food security[1]. However, it is difficult for small-scale farms and smallholder farmers to compete with larger, commercial enterprises on equal terms in global, regional or even local markets.

The increasing use of digital technology in agriculture has marked the start of a major transformation: Better services and products, innovations, enhanced decision making and increased profitability and productivity. But do small holder farmers really benefit equally, or even at all, from the benefits of data sharing? Moreover, do all stakeholders in the agricultural sector have the same access and control to these insights? What concerns do farmers have on such issues as data ownership, access and control, security and privacy?[2]

With personal data fast becoming the world’s most valuable commodity, more research needs to be done into the rise of Digital Feudalism and its societal impacts. Feudalism as a concept has its roots in medieval times, where serfs worked the land, creating value for the overlords and landowners who controlled it. Nowadays, when we refer to digital feudalism, we are referring to the rise in IoT and digital technologies, the increasing use of the internet to power and conduct our lives, and the data technology companies who profit from it.

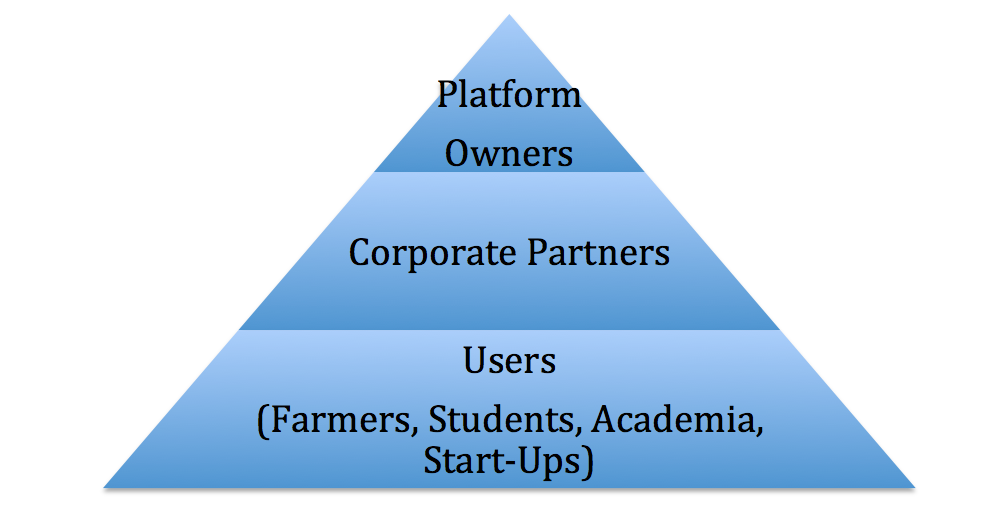

The new controlled commodity is user-created data. Worthless on it own, it can be argued, but valuable once aggregated. The “landowners” in this new digital landscape are exchanging services (social media, search engines…) for data, which once aggregated and controlled is worth many times more than the initial investment. Thus, user-focused social media giants and data collection companies are becoming the most mature data technology companies in our modern, data-driven economy, with the tech-elite becoming the new rulers of our increasingly technology dependent world[3] (see Fig.1).

The rise of Digital Feudalism not only raises questions over who controls, owns and benefits from the value of data, it also raises ethical and legal questions related to privacy, accuracy and accessibility. This, in turn, leads to questions around the rise of digital monopolies and the power imbalance that could create; as well as the resulting data asymmetry and its impact on the global society. It is essential that we advance the dialogue on developing ethical principles and solutions as a means to help address these issues.

Fig.1: Digital Feudalism class structure[4]

Digital Feudalism is not just limited to the obvious social media and consumer markets, but affects many domains, including agriculture. The rise of digitisation is not only a technical question. It also has social, ethical and legal implications, since the world of agriculture is quite diverse, composed of many different types of agricultural methods and farming realities.

In order to maximise their potential, it is important that digital solutions are designed with a view to the needs of farming communities. This is especially true in countries with very low literacy levels and limited knowledge of digital technologies, yet where the untapped agricultural potential remains among the highest in the world. This concern, coupled with the growing digital divide it is causing, serves to highlight the urgent need for developing ethical principles and guidelines for agricultural data.

in order to maximise its potential value: promote more effective decision making, foster innovation, and drive organisational change through greater transparency; data should be FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) and open as possible. FAIR data enables farmers to harness better decision-making tools, researchers to access information more readily, policymakers to make evidence-based investments, and other private or public sector and civil society stakeholders to develop services that will improve the overall efficiency of the food supply chain.

There is a pressing need to develop and adopt a conceptual framework for improving data management and governance, focused on consensus and promoting the advantages of a fairer sharing of the benefits associated with the use of agricultural data and information. Rather than leaving agriculture data management in the hands of the data aggregators; agricultural industries, producers and stakeholders should work together to ensure that the basic features of good data management such as trust, transparency, inclusiveness and fairness, become an integral part of agricultural data governance[5].

GODAN’s Data Rights and Responsible Data Working Group[6] aims to look at systems of governance that support a fairer, more equal distribution of benefits, where transactions are based on mutual interest and trust. Such systems can be implemented through laws and policies, as well as more informal codes of conduct, regulation and social agreements, depending on the individual situations and needs of the communities in question.

It should be possible to strengthen the agricultural sector – and by doing so, the corresponding supply chains - through greater collaboration, awareness of individual open data rights, ownership issues and possible solutions. In such a situation, external stakeholders would need to take into greater consideration the needs and rights of other parties involved, further strengthening and building trust. This would lead to a network that would work to the benefit of all actors (including small stakeholders), and enable inclusive participation in sustainable agri-food systems, through fairer data sharing.

The Agricultural Code of Conduct Toolkit is a flagship output of the GODAN/CTA Sub-group on Codes of Conduct. The online tool was created by GODAN, the Technical Centre for Agriculture and Rural Cooperation (CTA), and the Global Forum on Agricultural Research and Innovation (GFAR). Launched in May 2020, the Toolkit allows stakeholders to simulate and build their own agricultural data code of conduct, with consideration to other stakeholders in the chain.

While the practical benefits of such a tool are obvious, the Toolkit will also allow stakeholders to gain a better understanding of the differing needs and concerns of all actors, strengthening trust throughout the data value chain. The online Agricultural Codes of Conduct Toolkit was developed as a result of a consultative process involving the GODAN/CTA Sub-Group on Data Codes of Conduct, as part of a planned global collective action on Empowering Farmers through Equitable Data Sharing. It began as a review of existing guidelines and principles for farm data sharing, developing into a general, scalable and customisable code of conduct template that addresses the needs of all actors in the agricultural data ecosystem. Find out more at https://www.godan.info/codes[7]

Despite being voluntary and not legally binding, agricultural codes of conduct have the potential to contribute towards major cultural shifts. Data ethics cover the impact that all data activities have on people and society, as such all activities should be subject to ethical examination. It is essential to raise awareness about the ethical issues and legal frameworks – involving both personal and non-personal data – that arise from how data is collected, who it is shared with and what is shared[7].

Codes of conduct provide a solid framework for best practice in data management through the engagement of all stakeholders (including, and especially, farmers) in open dialogue to find solutions that address the needs of everyone involved.

The Sub Group on Data Codes of Conduct-led Agriculture Data Code of Conduct initiative[8] is an ongoing project. GODAN invites everyone interested to send feedback, examples of success stories or to get involved by contacting GODAN Data Rights Specialist Foteini Zampati [Foteini.Zampati@godan.info] and joining the GODAN Data Rights and Responsible Data Working Group.

Further Reading

[1]Smallholders, Food Security and the Environment: https://www.ifad.org/documents/38714170/39135645/smallholders_report.pdf

[2] https://www.godan.info/news/godan-blog-codes-conduct-better-ag-data-management

[3] https://qz.com/1706221/don-tapscott-on-using-blockchain-to-take-back-your-digital-identity

[4] https://towardsdatascience.com/digital-feudalism-b9858f7f9be5

[5] http://farminstitute.org.au/LiteratureRetrieve.aspx?ID=162392

[6] https://www.godan.info/pages/data-rights-and-responsible-data-working-group

[7] https://www.godan.info/codes

[8] https://www.godan.info/working-groups/sub-group-data-codes-conduct